How New Zealand changed their voting system

|

|

By Alexandra Clarke

Politicians or used-car salespeople: Who do you trust more? New Zealanders polled in 1990 were hard pressed to name a preference. Decades of economic uncertainty mixed with broken election promises had left people frustrated with their political representatives, their Parliament, and their two-party system. So in 1993, New Zealanders voted to change their electoral system from the traditional first-past-the-post (FPTP) method to mixed member proportional representation (MMP).

Just like in Canada, New Zealand’s FPTP electoral system stemmed from its British colonial legacy. FPTP can work well in a two-party system, but New Zealanders felt their two main parties - National and Labour - didn’t represent the population’s diverse political needs and preferences. Voters who looked to alternative parties found that their votes made little to no difference, and they often had to resort to strategic voting to keep their least-favourite option out of office. Starting to sound familiar?

Time for change

Frustrations with FPTP led to the creation of a Royal Commission on the Electoral System. Its 1986 report recommended that New Zealand adopt the German-style MMP, in which each elector gets two votes - one for a local candidate, and one for a party. Neither of the two major parties were particularly pleased with the Commission’s recommendation, but each ran their 1990 election campaigns with a promise to hold a referendum on the issue.

The 1992 ‘Preferendum’

In 1992, facing increasing public pressure, the governing National party reluctantly agreed to hold a non-binding referendum to gauge public support on electoral reform. In a two-part poll, voters were asked:- Whether they wanted to retain the current voting system or change it; and

- If they voted to change the system, which system they would choose. They were given four options: mixed member proportional representation (MMP), the single transferable vote (STV), supplementary member (SM) or preferential vote (PV)

The government promised that if there was widespread support, they would hold a binding referendum the following year asking voters to choose between FPTP and the most popular reform option.

The results came in loud and clear: 85% of voters wanted electoral reform, and 70% favoured MMP, a type of proportional representation. As Labour Leader Mike Moore put it, “The people didn’t speak on Saturday. They screamed.”

Educating voters on their options

“Mixed member proportional representation,” “first past the post”: For the average voter, these terms can sound complex and abstract. To make sure voters knew what they were going to the polls for, the New Zealand Electoral Commission (similar to Elections B.C.) ran an official information campaign. They used a non-partisan, neutral tone, and the information they provided focused strictly on the possible outcomes of each system. It included:- Comparing the number of MPs

- Proportionality

- M?ori representation

- Propensity for coalitions under each system

- Representation of minorities and geographic regions

Let the lobbying begin

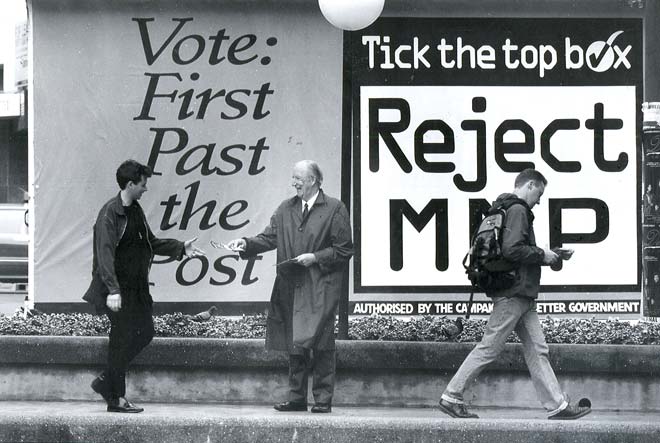

Two main lobby groups emerged after the 1992 referendum, and they fought tooth and nail to win votes. The Campaign for Better Government (CBG), a predominantly corporate-sponsored group (set up by Peter Shirtcliffe, head of Telecom) worked to maintain FPTP, whereas The Electoral Reform Coalition (ERC), led mainly by academics, trade unionists, and members of the Women's Electoral Lobby, worked to promote MPP.The CBG campaign reportedly spent $1.5-2 million on its efforts. They hired advertising firm Saatchi & Saatchi to spearhead their campaign, which focused primarily on convincing voters not to vote for MMP (rather than on the advantages of FPTP).

The ERC reportedly only spent between $150-300k on its campaign, but was well-organised and had strong links in community networks. Their campaign focused on convincing “everyday New Zealanders” that MMP was in their interest, as well as creating a brand around MMP and the kind of voter who supports it.

Main talking points focused on by each side

| Anti-MMP | Pro-MMP |

| Negative consequences Drawing on imagery and text that stoked concerns about the “unknown” reality of MMP -- that it is too risky, could lead to government instability and extremists represented in parliament. |

Proportionality Messaging that portrayed that proportional representation systems ensure votes “count” and that vote translate directly into electoral seats. |

| Hidden power Stoking fears that MMP would lead to “post-election manoeuvering”, “horse-trading” and “back-room dealing”. |

Representation Through the use of images depicting “everyday New Zealanders” as well as Kate Sheppard (the face of NZ’s Women’s Suffrage Movement) -- drawing upon New Zealanders’ pride in providing a voice for women and minority groups. |

| Accountability Portraying MMP as a system that encourages “fat cat”, power-hungry politicians, and that would transfer power from voters to parties. |

Widespread support Evoking “David and Goliath” and big business vs. the working class, appealing to the shared identity of their audience and othering the (political) elite. |

(Credit: Mark Round, Dominion Post)

A vote for change

Despite the significant spending imbalance between the two lobby groups, electoral reform passed with 54% of the vote. The referendum was held at the same time as the 1993 general election, which helped catapult voter turnout to a whopping 85%.With MMP the clear winner and only three years until the next election, change happened quickly. New parties emerged, electoral and parliamentary rules and procedures were overhauled, and a massive public information campaign informed voters about the new system.

The 1996 general election was the first held under the MMP system. It showed a clear break from the status quo – The Alliance and New Zealand First, which had each held only two seats in the old parliament, increased their seats to 13 and 17 respectively. A brand new party, ACT New Zealand, took eight seats.

2011 check in

Another referendum was held in 2011 to check in on voters’ satisfaction with MMP. A similar public education campaign was run, this time with the help of videos, a website, social media, and an interactive assessment tool where voters could indicate which of five criteria (Accountability, Proportionality, Effective Government, Effective Parliament, and Representation) they valued more or less. Based on their results, they were shown which electoral systems were more or less consistent with their values.The referendum showed a clear preference for maintaining MMP, with 58% of voters stating their satisfaction with the system.

What now?

New Zealand has now had seven elections under MMP. MMP’s impact on New Zealand’s parliament has been profound, both in terms of the number of parties represented and a high degree of proportionality. Between six to eight parties have been represented in parliament at any one time, and there are more women MPs (approximately 30%), M?ori MPs (approximately 20%), and Pasifika and Asian MPs. Neither Pasifika nor Asian MPs were present in Parliament in 1990, but by the 2008 election, they made up five and four per cent of the House respectively.New Zealand is no exception: Countries with proportional representation are more likely to have smaller parties represented in their legislatures, to have multi-party governments, and to have representation from a variety of social, political and ethnic groups.

What does this mean for B.C.?

If B.C. wants electoral reform to pass, we should heed some valuable lessons from New Zealand’s experience.A two-question ballot is best.

It’s not enough to give voters one binary choice; they need the opportunity to express their (dis)satisfaction with the status quo and have a say in what comes next.

A well-funded public education campaign is essential.

Researching complex electoral systems is the last thing busy voters need, and lobby groups will do everything they can to spread (mis)information that benefits their cause. Elections B.C. should be given the resources to educate voters on their options in a neutral, interactive and comprehensive way.Grassroots community groups can make a huge impact.

The pro-MMP campaign had strong links to community networks and gave its individual branches lots of autonomy on fundraising, advertising, and outreach efforts. They educated their volunteers well and developed a widespread network of knowledgeable speakers who were regularly invited to speak at church groups, Rotary and Lions clubs, trade unions, and on chat radio. Grassroots groups across B.C. should be given autonomy to drive the movement for electoral reform in their communities, as well as empowered to recruit and train a cadre of educated advocates.If they go low, we go high (but not too high).

New Zealand’s pro-FPTP group ran a solely negative campaign. The pro-MMP campaign took a did the opposite -- even though negative campaigns had often proved more successful in past elections. While it is important to focus on the benefits of electoral reform, outlining the disadvantages of FPTP is equally as important to persuading voters.Sources:

https://mro.massey.ac.nz/bitstream/handle/10179/4734/02_whole.pdf

http://ro.uow.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1464&context=buspapers

http://www.campaignbrief.com/2011/09/saatchi-saatchi-nz-creates-too.html